DECIPHERING THE EVOLUTIONARY HISTORY OF THE IRISH ELK WITH SOME HELP FROM GENETIC GENEALOGY

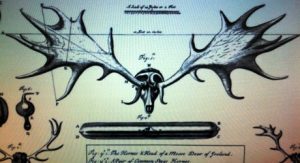

The following picture was copied from the article “A discourse concerning the large horns frequently found under ground in Ireland, concluding from them that the great American deer, call’d a Moose, was formerly common in that island” by Dr Thomas Molyneux 1697

PREAMBLE

Denis Kelly (1798-1877) (Ui-Maine #44) was a well known Hy- Manian. His ancestor Colonel Charles O’Kelly (1621-1695) (Ui- Maine #39) wrote the Death of Cyprus (A History of the Williamite Wars). Denis O’Kelly was a magistrate, member of parliament for Roscommon and an enthusiastic historian. Denis lived at Castlekelly (Aughrane) Ballygar. He is also remembered for the erection of 93-foot stone tower in about 1867 in the Killeroran Graveyard (just outside Ballygar) in dedication to his family (wives and daughters). The height of the tower meant the memorial could be seen from his Ballygar residence.

Over 150 years ago Denis Kelly authored a paper on a gravel esker near Gallagh Castle. An esker is a low-lying ridge of sand, gravel and boulders deposited by water flowing beneath a glacier that became exposed at the end of the last ice age, around 10,000 years ago. The best known esker in Ireland is the Esker Riada. It is a collection of eskers that pass through the counties of Dublin, Meath, Kildare, Westmeath, Offaly, Roscommon and Galway. The Irish name ‘Eiscir Riada’ means ‘divide’ and ‘road’. In 123 AD, Ireland was divided into two political entities along the line of the eskers – ‘Leath Cuinn’ (‘Conn’s Half’) to the north, and ‘Leath Mogha’ (‘Mogha’s Half’) to the south. Because the slightly higher ground of the Esker Riada provided a route through the bogs of the Irish midlands it has, since ancient times, formed a highway joining the east and west of Ireland. Indeed, its ancient Gaelic name means ‘The Great Way’. The Great Highway provided a link between Durrow Abbey and the monastic settlement of Clonmacnoise, constructed at the point where the River Shannon passes through the Esker Riada. We all should know that the Annuals of Clonmacnoise provide a window to some of the history of the Ui-Maine Kellys.

In contrast with the surrounding bog-lands, the glacial sands of the eskers provided well drained and relatively good quality land for development (agriculture and building). To this day, the Esker Riada continues to serve as a highway, the main N6 Dublin to Galway road still closely follows it. The eskers have been a valued source of building material, with sand and gravel extraction being commonplace. However, the negative environmental impact of such operations is now being realized and this, along with a developing awareness of the ridge’s natural beauty and its significance in Ireland’s history, has led to increasing restrictions. County Offaly County has moved to give the ridge protection in its County Development Plan, and has gone so far as to press to have the Esker Riada recognized as a World Heritage Site.

Back to Denis Kelly’s esker. He said it was over 300 yards long and looked like a continental vineyard (wishful thinking perhaps). The eastern end of the esker was cut off by a mound that was the remains of the ancient Castle Gallagh once the seat of the O’Kellys of Ui-Maine. Denis O’Kelly continues his description with a note that the new mansion at Gallagh was built from the ruins of the ancient castle. Denis was also an amateur archaeologist. In another one of his articles he describes the excavation of a lake near Strokestown (Another O’Kelly strong hold). Seems he was there at a time when the falling lake levels started to reveal antiquities including the remains of a fabled Irish Elk. He prepared some of these papers with a distant cousin Richard Kelly. Richard was another prominent Ui-Maine Kelly who was the founding editor of the Tuam Herald and the Journal of Galway Archaeological and Historical Society. Here is a story about the Irish Elk and how genetic genealogy has been used to help decipher its past. It has some parallels as to how genetic genealogy is also used to decipher the history of the Ui-Maine Kellys and other family genealogies.

DECIPHERING THE EVOLUTIONARY HISTORY OF THE IRISH ELK WITH SOME HELP FROM GENETIC GENEALOGY

This story about the pre-historic Irish Elk will help explain the usefulness and current progress that has been made using genetic analysis to help human genealogical research – so called genetic genealogy. It demonstrates how genetic genealogy may be used to confirm or re-construct existing pedigrees; animal or human for that matter.

The key drivers behind the prevalence of genetic tests are that tests are getting cheaper and that with more individuals testing the sample size and usefulness of the results are increasing. Basic entry level tests are $200-$400 and some say less than $5,000 for a whole genome; that in theory can be sequenced in 24 hours. Ten years ago that was nearly impossible to even think about unless you were a billionaire.

Genetic techniques have revealed that the Irish Elk was not a real Elk or for that matter exclusively Irish. Because Irish Elk were obscure, regal and strange they gained an almost mythical reputation. Not that different to some of the characters of Irish history; the founders and kings of Irish history, some regal some mythological. The mystique of the Elk is completely re-enforced by viewing their remains. The National Museum of Ireland has 10 complete skeletons. They look a bit like dinosaurs.

Genetic biologists analysed DNA from fossilised Irish Elk. One sample was taken from bones found in a cave in Waterford (Ballynamintra Cave). The DNA results showed that the Elk’s closest living relative was not as previously believed to be an elk-like creature (such as the red deer or the Moose), but a fallow deer (Dama sp). The fallow deer is a much smaller species but the DNA reveals the strongest match is between the Irish Elk and the fallow deer. The reason they were called Irish Elk is because their skeletons used to turn up in lake sediments under Irish peat bogs (and that was all that was known of them by modern man because they became extinct in 5,000BC). We now know that their actual range extended from Ireland to western Siberia and parts of Asia.

The Irish Elk was designed for dominance. A mature stag stood 7 foot and weighed more than 500kg. But the most impressive and distinctive feature was his antlers. The Elk had a massive rack that measured 12 foot across from tip to tip and weighed nearly 100-pounds. For centuries people lusted after these antlers. Nature’s ultimate status symbol. Kings hung them in castles and people used them to decorate bridges and gates. Nineteenth-century fossil hunters dredged every Irish peat bog looking for them for fascination and money.

The modern records suggest the first Irish Elk remains, part of a skull, was discovered in 1588 in County Meath. Since then a lot of time and effort has been spent trying to figure out what they looked like, not just the bones but the flesh as well. This has been a work-in-progress ever since for naturalists, taxidermists and biological scientists. A drip feed of information from a range of different sources and researchers has helped to solve the puzzle of the Irish Elk. But none has been more powerful and precise than DNA data.

The Irish surgeon Dr Thomas Molyneux was one of the first naturalists to write about the Irish Elk. In 1697 he published a paper in Philosophical Transactions called: “A discourse concerning the large horns frequently found under ground in Ireland, concluding from them that the great American deer, call’d a Moose, was formerly common in that island” [close inverted commas]. He accepted that Irish Elk had completely vanished from Ireland; but it would have been considered heretical to suggest that one of god’s creature could be made extinct, rather he was happy to believe that the species had in fact migrated to North America and shrunk a little. Over there people called it a Moose (the Moose is actually more elk than deer). Others thought the Elk was a giant rein deer. The Victorian period scientists found the Irish Elk very perplexing and believed that its ever-evolving antlers were simply a liability and that this somehow completely and conclusively disproved Darwin’s theory of natural selection.”

Darwin actually said that the Irish Elk’s antlers were “splendid accoutrements” for attracting mates. Three-dimensional aphrodisiacs to lure females to their territory (but Darwin also admitted he had no real evidence in favour of this belief – it was just a hunch).

In 1812 Barron Georges Cuvier wrote in his book “Research on fossil bones” that the Irish Elk had died along with the mammoth during the last glacial freeze-over about 10,000 years ago. Subsequent isotopic carbon-dating has proved that the Irish Elk out-lived the mammoth and lived contemporaneously with pre-historic humans as late as the early Holocene about 7,000 thousand years ago – that’s circa 5000BC. So how and why did this resilient species, the stag or all stags manage to survive the ice age, live another 3,000 years and then seemingly abruptly die-out? DNA evidence has helped solved this puzzle.

In 1974 the eminent evolutionary scientist Stephen Jay Gould published a land-mark essay on the Irish Elk. Theory A was that the size of the antlers led it to extinction. The sheer size and weight of the antlers were too massive for the Elk’s 5kg skull to support. Theory B was that with the advent of agriculture and more intensive settlement and development of Ireland the ecology of the land systems changed and the Irish Elk failed to adapt to maintain its sources of phosphorous and calcium that were required for its nutrition; including that needed to regenerate new antlers each year. A lot of fuel is required to grow one-hundred-pound antlers every year over just four months. As a result the species developed osteoporosis and perished. A combination of reduced feed, humans and osteoporosis appear to have done the beast in. That’s Theory B and that sounds about right.

Back to the DNA evidence, if the Irish Elk was essentially a giant fallow deer the rule is that it should mate like a fallow deer. Contemporary biologists have shown that the fallow deer is one of the few species of deer in which females travel in a herd to select a stag. Back to the antlers, female fallow deer are attracted to stags that have impressive racks. An alpha stag mates with as many females as possible and that one stag may produce 30-100 fawns a year. A fallow deer stag occupies territory called a “lek”. During mating season the stag flashes his antlers to attract a doe or more than one doe to his “lek”. If another buck or bull stag comes into that “lek”, the alpha stag will force the pretender away. There may be some confrontation. They carry-on a display like a ritualised dance and body slam; usually with no real hurt just dented pride. The chances are high that the Irish Elk was just the same. His antlers were used to attract females to his “lek” and his body size to repeal his rivals. Only the biggest, widest antlered stags actually got to mate, so the genetics always headed in the direction of bigger antlers. That was life. The sexual nature of those “splendid accoutrements” is now supported by deer research that shows that antler growth is propelled by testosterone. Testosterone levels steadily increase before the mating season and thereafter declines which triggers the shedding of the antlers.

So some of the mystery of the majestic Irish Elk is revealed through the window of DNA and genetic genealogy. Information derived from DNA matching allows comparative research; analogous, deductive and inductive reasoning to remove the mask of obviousness and non-obviousness. Similarly, genetic genealogy is used today to assist researchers, scientists and amateur enthusiasts (so-called citizen science) to reveal the history of our human ancestors and their family histories. The DNA approach to genealogy can help solve some of the puzzles created by incomplete and incorrect written records or no records at all and to expose past indifferences to plausible and implausible ancient pedigrees (Saxons, Basques, Gauls, Celts, Conn, the Three-Collas, Niall, Maine Mor and the Ui-Maine Kellys, the list is long).

In addition to ancient Irish Elk, genetic genealogy has recently been used with great success to confirm and enrich the history of the likes of Richard III, Ned Kelly and the Irish Bear. Genetic genealogy has a lot to offer to help unscramble the past.

REFERENCES

[1] www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/mammal/artio/irishelk.html

[2] Still life (Adventures in taxidermy) Melissa Milgrom (2010)

[3] www.wikipedia.org/wiki/Irish_elk

[4] Denis Henry Kelly collection: Kelly Irish Manuscripts in English, John Rylands University Library, University of Manchester http://archives.li.man.ac.uk/ead/html/gb133engmss478-507-p1.shtml